Navigating Picky Eating (Without the Panic!)

by Roxy Krawczyk, M.A. Ed.

“My kid used to eat all kinds of foods, even broccoli! Now all they want is crackers and cheese sticks. What happened?!”

If you find yourself asking this question, you’re not alone. Just about every parent experiences this moment as they watch their young child shift from an adventurous eater to a far more selective one.

The good news is that there is a good reason for your child’s sudden food finickiness! And there are some easy things you can do to help guide them back to the land of variety. But first, let’s break down why children tend to go through a picky eating phase so that we can better understand how to help them through it.

Food neophobia — the predisposition for rejecting unfamiliar or unknown foods — is indeed a normal human developmental phase. Typically, it hits its peak when a child is between 2 and 6 years old. (Sound familiar?)

Several biological factors play into this spike in food sensitivity. First, young children likely taste bitter and sweet differently than adults do. They are more sensitive to compounds that give foods a bitter flavor (think cruciferous vegetables and some cheeses), which means they may notice bitter flavors that are too faint for adults to detect.

At the same time, children seem programmed from birth to seek out sweet. Studies show that young children actually appear to have a higher threshold for sweetness, meaning that they can’t detect the sugar in a food until it is more intense. So just as a child might taste bitter notes in a food when an adult does not, an adult might taste more sweetness in their food than their child does.

From an evolutionary perspective, these predispositions are actually beneficial to our species’ survival (as is a general wariness of new foods!). Bitterness in plants is an indicator that the plant contains compounds which can reduce digestibility and/or cause illness. Children are even more susceptible to digestive upset than adults, and their heightened sensitivity to bitter flavors offers them increased protection.

Alternately, sweetness in a plant is a sign of its ripeness, which is the time when it is least likely to contain toxins or compounds that reduce digestibility. In other words, sweetness is one sign that a plant is safe to eat. Sweetness is also an indicator of more calorie-dense foods. Since children have a higher need for energy-dense food than adults, it makes sense why they would find sweet foods extra appealing.

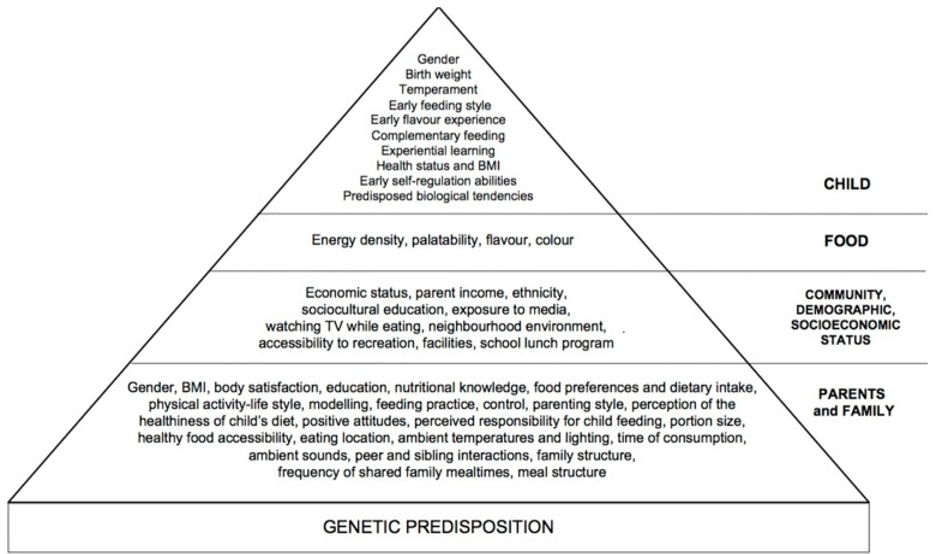

So there is a general biological basis for children

having different food preferences from adults. But it doesn’t stop there! There are, in fact, a multitude of interrelated biological and environmental factors that influence a child’s eating tendencies:

De Cosmi V., Scaglioni S., Agostoni C. Early taste experience and later food choices. Nutrients. 2017;9:107

And based on their individual biology, some children are even more predisposed to food sensitivities than others. Some carry genes that heighten their sensitivity to bitter or sweet flavors. Others are highly sensitive to certain sensory properties of foods, such as smell, texture, or consistency.

However, parents can take comfort in the fact that regardless of individual differences, all children go through changes in their relationship with food. In fact, studies show that young children around the world demonstrate a cross-cultural tendency to resist and even refuse new foods. Why?

As children become more aware of the sensory properties of foods, they also begin to more closely scrutinize all foods. Much of this stems from a biologically-based fear response. During this period, children develop a much narrower category of “safety” for foods, which often focuses on predictability. Foods that are always the same in texture, flavor, and consistency (i.e. crackers) are highly predictable and thus feel safe. In contrast, foods that appear varied — or ones that look the same but have a different flavor or texture from one to the next (i.e. berries) — get lumped into the unpredictable and unsafe category. Even foods that were previously liked may get moved into the refusal category if it does not match the child’s new narrower criteria for “safe” foods.

The good news is that children can (and do) learn to like new foods! It just takes time and consistency. Research shows that it can take up to 15 (or even 20) exposures to a new food before a child decides to trust it. In fact, even after a child is willing to taste a new food, it may still take up to 15 more exposures for a child to decide they officially “like” it.

Uh-oh. Does that mean we must force our kids to eat steamed broccoli 30 more times before they’ll decide to like it?

Not at all!

Firstly, not every “exposure” to a new or refused food has to involve eating. The ultimate goal is indeed for your child to taste the food so that they can start to get familiar with its flavors and textures. So yes, it is important to continue offering your child the food at meal and snack times.

But even if your child staunchly resists eating that delicious lemon roasted broccoli at dinner tonight, you can still take advantage of the meal to show how you eat and enjoy it. Watching a trusted adult model their positive relationship with a new or refused food is an important form of exposure. (So remember to cook it in ways and recipes that you like, too!)

You can also use non-mealtime activities to get your child more interested in and comfortable with new or refused foods. One fun way to do this is to involve your child in learning activities based around food, such as reading books, singing songs, or sensory play. Another highly effective strategy is to invite your child to participate in the growing, harvesting, and/or preparing of their food. Doing this work together creates lots of pressure-free opportunities for children to see, feel, talk about, and even taste meal ingredients. It also allows you to naturally model your own familiarity, interest, and enjoyment of different foods.

Worried about finding time to start a family garden amidst your already busy schedule? Remember to utilize the resources you already have! Ask your local librarian for some great books. Invite a family member or friend to teach your child how to make their favorite dish. Explore a new world cuisine during family dinner! There are so many ways to build in exposure to foods in different forms, contexts, and cultures that can be both easy and fun.

For example, at A.L.M.A., we engage children in positive food exposure all day, every day. We are constantly talking about, learning about, singing about, reading about, and playing about food! We plant, tend, harvest, prepare, and eat our food together with the children. And we very intentionally include foods from a wide variety of cultures on our menus. Parents will often report back to us with shock that their child ate (and enjoyed!) something new at home, but we are not surprised! All of the work we do to build familiary and trust between us, the children, and our food makes them feel safe and encourages them to be brave.

It is important to note that while authoritative encouragement can be helpful, trying to pressure children into eating is generally counterproductive. Overt attempts to control what, when, or how much a child eats tend to create a power struggle. Increasing conflict over food then feeds into more fear-based responses and prevents your child from making consistent progress.

The best thing parents and caregivers can do is to control the environment that surrounds food at home. What does that mean? For one, don’t offer foods you don’t want kids to choose! Instead, provide lots of access to healthy foods and offer children genuine choice. Try the “Division of Responsibility” feeding model in which you choose which foods to offer for a meal, and your child freely chooses which to eat. You don’t have to wax poetic trying to convince your child to eat the broccoli. Just spending some intentional, screen-free time together during meals and modeling your own enjoyment of foods is enough.

Eating with your child also allows you to model different food vocabulary, which is more important than we often realize! There are so many ways to talk about foods that we like and foods that we don’t. However, many times children will simply say “I don’t like it” when they don’t want to eat a food, even if the problem is actually just that they are tired, not hungry, or wanted something different to eat.

We can use curiosity questions to help our children zero in more specifically on how they are feeling. Then we can model different vocabulary by talking about our own experiences with food. Helping our children to understand and express themselves more accurately can help avoid reinforcing the idea of “I don’t like it” in their minds (and ours!).

Parents are under an enormous amount of pressure to feed their children “well.” It makes sense why you might panic when you see your child’s accepted food list begin to quickly dwindle. But it is important to remember that a period of picky eating is normal in young children. And, in general, the best thing parents can do is to keep calm and stay the course. Studies assure us that kids will eventually accept new foods if we can just be positive and persistent.

References

Dewar, Gwen, Ph.D. “The Science of Picky Eaters: Why Do Children Reject Foods?” Parenting Science, https://parentingscience.com/picky-eaters.

DiGiulio, Sarah. “What Makes Kids Picky Eaters — and What May Help Them Get Over It.” NBC News, 10 Feb. 2018, www.nbcnews.com/better/health/what-makes-kids-picky-eaters-what-helps-them-get-over-ncna846386.

Loughborough University. “Food Refusal.” Child Feeding Guide, 2017, www.childfeedingguide.co.uk/tips/common-feeding-pitfalls/food-refusal/#:~:text=Why%20do%20children%20often%20refuse,had%20to%20scavenge%20for%20food.

Scaglioni, Silvia et al. “Factors Influencing Children's Eating Behaviours.” Nutrients vol. 10,6 706. 31 May. 2018, doi:10.3390/nu10060706.

About the Author

Roxy Krawczyk is a Montessori teacher, education consultant, and freelance writer. She holds Montessori certifications in both early childhood (AMS) and adolescent education (AMI), as well as an M.A. in Education and a B.A. in English. Roxy has ten years of experience teaching in the classroom, and she has spent the last five years consulting for early childhood programs. She loves using her passions for education, research, and writing to help parents gain new insight into the ever-changing job of raising small humans!